New Horizons' Hit 150 million KM Away Today, Attempts Photo of Voyager 1

Share

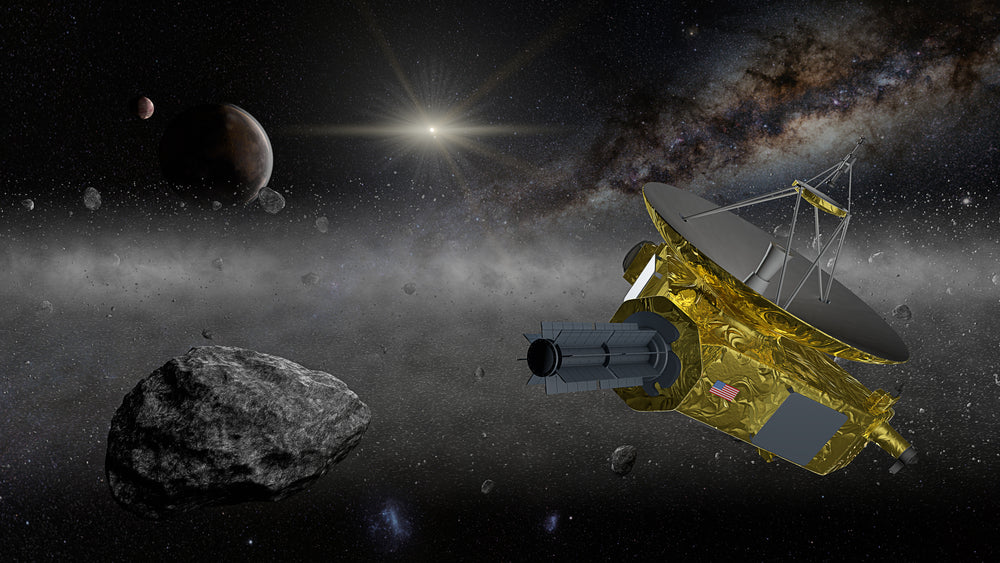

New Horizons, a NASA spacecraft and frontier mission probe designed to explore the deep solar system, has reached some rare space.

Early Sunday morning, New Horizons reached 50 astronomical units or about 7.5 billion km from Earth. A single AU is a distance from Earth to our sun, about 150 million kilometres - and 50 AU has been achieved by only four other operational probes in the history of mankind.

Via NASA:

Here’s one way to imagine just how far 50 AU is: Think of the solar system laid out on a neighborhood street; the Sun is one house to the left of “home” (or Earth), Mars would be the next house to the right, and Jupiter would be just four houses to the right. New Horizons would be 50 houses down the street, 17 houses beyond Pluto!

The milestone is one to be celebrated, as the craft has given us the first close-up look of Pluto mid-2015 and shortly after snapped images of Arrokoth - a small Kuiper Belt object in the far depths of the solar system.

And as such, New Horizons celebrated by taking a photo of Voyager 1, the farthest human-made object and first spacecraft to actually leave the solar system more than 152 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun—about 22.9 billion kilometers from Earth.

Voyager 1 itself is about 1 trillion times too faint to be visible in this image. Most of the objects in the image are stars, but several of them, with a fuzzy appearance, are distant galaxies. New Horizons reaches the 50 AU mark today and will join Voyagers 1 and 2 in interstellar space in the 2040s.

"When I stop from all the day-to-day hubbub of planning and managing and data analysis and budgets and all those things, just stop and think what we've accomplished as a team, it's really inspiring," said New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern based at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. "Sometimes I want to pinch myself."

New Horizons is well on its way to reaching its full potential and there's plenty of reasons to look ahead. The probe's remarkably healthy and could continue exploring its exotic surroundings many years into the future, despite streaking through space for 15 years Stern said. "We have power and fuel to go on into the late 2030s," said Stern. "So, we're kind of halfway into this mission, in terms of what's possible from an engineering standpoint."

A radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) powers New Horizons by harnessing the energy of radioactive decay to produce electricity. The Deep Space Network has used the same RTGs on all NASA deep space probes, including the four probes that crossed the 50-AU threshold before New Horizons — Pioneer 10, Pioneer 11, and Voyager 1 and Voyager 2.

Despite Pioneer 10 and 11 ceasing operations, the Voyagers continue to explore interstellar space today, almost 40 years after launch. Voyager 1 is currently about 152 AU from Earth while Voyager 2 is nearly 127 AU from us.

Three decades have gone into making New Horizons' journey, and it is full of twists and turns.

Since the late 1980s, Stern and his colleagues have been developing a Pluto project, but the $720 million mission didn't gain official approval until the early 2000s.

Launched in 2006, the New Horizons probe was tasked with performing the first-ever flyby of Pluto. Despite NASA's Hubble Space Telescope's best efforts, this distant dwarf planet appeared no more than a fuzzy blob in even the best photos since its discovery in 1930.

A remarkable flyby of Pluto took place on July 14, 2015, with the New Horizons probe zooming within 12,550 kilometres of the planet's frigid surface. During this close encounter, the probe's observations have revealed Pluto as a real landscape featuring towering water-ice mountains, bizarre "bladed terrain," and a giant nitrogen-ice plain that makes up one lobe of Pluto's famous "heart."

Once the flyby was complete, New Horizons continued to study its surroundings, the ring of widely scattered, frigid objects beyond the orbit of Neptune: the Kuiper Belt. On Jan. 1, 2019, the probe performed its second close flyby, this time of a small Kuiper Belt object, after studying its local environment and observing a number of Kuiper Belt objects (KBOs) from a distance.

The New Horizons probe spent less than a day in close proximity to Arrokoth on New Year's Day when it was more than 1.6 billion km beyond Pluto's orbit at the time. One of the most surprising aspects of the latest data from the probe was its approach to Arrokoth, which appears to be a 36km wide, reddish space snowman.

New Horizons' observations confirm that Arrokoth is a very primitive, primitive object left from the dawn of the solar system. Its two spokes are likely to have been distinct objects, which merged in a gentle merger, mission team members have said.

"Both of our main targets turned out to be scientific wonderlands — beyond our wildest expectations in both cases," Stern said.

What’s Next for New Horizons?

With Subaru Telescope data and New Horizons team data, they have already begun searching for another Knowledge-Bound Object along the spacecraft's path. Given how thinly populated the Kuiper Belt is, a third flyby is a longshot, but Stern and his colleagues are working hard to increase the odds as much as possible.

As an example, mission team members J.J. Kavelaars and Wes Patrick began using machine-learning techniques to discover KBOs from a distance and within close proximity.

When they "reran the 2020 search data through their new software tools, it not only worked 100 times faster, but it turned up dozens of new KBOs that human searchers had not found in the search images!" wrote Stern in last month’s mission update. "We'll be taking advantage of this important new tool again later this year, and next year and after that as well."

The spacecraft will have a lot of work ahead of it in the coming months and years even if a suitable fly-by target doesn't emerge. So far, the probe has studied 31 KBOs and will examine three more next month if everything goes according to plan.

The May campaign will be "another brick in the wall of building up a statistically relevant collection of KBOs that we have studied in ways that you cannot do except by being in the Kuiper Belt, either by dint of the close range or as a result of the different angles that we see things at," Stern said. "We're building up this database. It's a legacy." Neptune and Uranus are still being observed, and new details about their Kuiper Belt environment, which is unknown in our solar system, will be collected.

So long as New Horizons stays healthy and NASA continues to grant extension requests, it will inspire scientists to explore the universe beyond the Kuiper Belt, about 70 AU from the sun. The New Horizons mission is likely to reach its boundary in the late 2020s and will likely be able to reach around 100 AU by the time its power runs out in the late 2030s, confirming its reputation as an explorer of historic proportions.

"We said we would build a spacecraft that could fly across the solar system and explore new worlds and we did that, and we're still doing that. But when I utter the words — they sound like science fiction, but they're not."