Sorry, There's No 9th Planet Hidden Away In Deep Solar Space, Study Says

Share

Is there a mysterious planet brooding about in the depths of our solar system?

Well, there's a gravity signature in the depths of our solar system past Neptune's orbital path. And folks really like speculating its a planet. But new research denies the presence of a hypothetical dark planet, calling it a "statistical mirage".

Ouch, take that.

The first instance of a 9th planet in our solar system came from a group of space rocks huddled unusually close together in a shared orbit. Hard to spot objects outside of Neptune are called "trans-Neptunian objects" (TNOs).

Objects like the rock huddle reflect such little light that they blend into the cloak of space or into the bright background of stars and galaxies. So much so that only a handful have been identified and catalogued.

A TNO that will ruffle a few feathers is Pluto, the one-time classified dwarf outside Neptune.

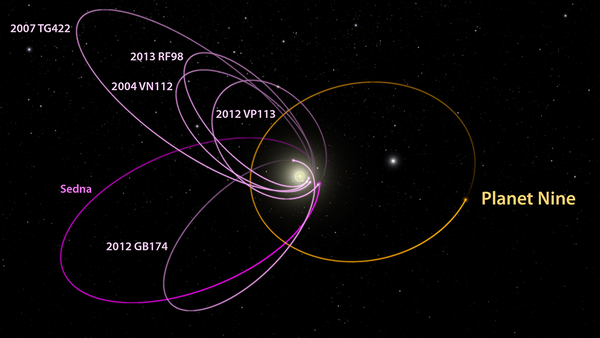

But in 2016, astronomers Konstantin Batygin and Mike Brown of the California Institute of Technology noticed that six TNOs, including the dwarf planet Sedna, all had long elliptical and "eccentric" orbits pointed in the same direction. Eccentric means that their most-distant points are much further from the sun than their closest points to the sun.

In a 2016 paper published in The Astronomical Journal, Batygin and Brown wrote that a planet with a mass of around 10 times that of Earth, way further out than Pluto, and following a long elliptical path around the sun, could explain the apparent clustering. Over time, they argued, its large gravity would have pulled these six TNOs into their clustered orbits.

But in a new paper, a large collaboration of researchers suggest that the TNOs aren't particularly clustered — they just look that way because of where Earthlings are pointing their telescopes.

The researchers took a sample of 14 very distantly orbiting, TNOs and assumed they were part of a mostly unseen larger family of objects, which they almost certainly are. Then they analyzed how much time telescopes had spent pointing at different parts of the sky. They found that astronomers might detect this particular collection of objects if all the TNOs on the outermost fringes of the solar system actually had a fairly uniform distribution — anywhere from 17% to 94% uniform. (A 100% uniform distribution would mean that TNO orbits are evenly spaced around the sun.) In other words, the extreme TNOs (ETNOs) might seem to be clustering, but that's only because telescopes have, on average, concentrated their attention on that part of space.

In essence, such uniform distribution would not fit the Planet Nine hypothesis.

This statistical analysis is similar to the sort of gut checks opinion pollsters do all the time. If a survey of a few hundred Americans found that country music was the favored genre of 55% of people, but then a closer look at the data revealed that 40% of respondents happened to be from Nashville, the pollster might adjust the data to account for the fact that that the sample was so heavily weighted toward one area of the country. In doing so, the pollster might find that the huge preference for country music disappears.

Dave Tholen, a University of Hawaii astronomer who searches for TNOs using the Subaru telescope on the summit of Mauna Kea in Hawaii, and who was not involved in the study, said there's still too little data for anyone to be drawing any firm conclusions about Planet Nine.

"We have a classic situation that I might describe as 'the statistics of small numbers.' One discovery can't align with anything. Two aligned orbits could easily be a coincidence. Three aligned orbits might raise the question, but certainly isn't enough on which to hang your hat. How many aligned orbits do you need before the chances of it being a coincidence drop to a convincingly small number? And what constitutes 'alignment'? Do they need to be within 10 degrees of each other? 30 degrees? 90 degrees? My own feeling is that we're still in the 'suggestive' stage."

The clustering of TNOs suggests there might be a planet tugging on them, making it a hypothesis worth exploring. But the clustering seen so far is not strong evidence. On the flip side, the new study can’t rule out Planet Nine either, Tholen said. Efforts underway right now will dramatically expand the catalog of known TNOs, and provide firmer ground for any claims on the subject, Tholen said. "Progress comes slowly," he said. "Any paper reporting on simulated surveys will always be out-of-date as long as we continue our observational work, because they won't include our latest sky coverage."

His team, Tholen said, works to observe the sky uniformly "specifically to avoid the sort of… bias" at the heart of the new paper's argument.

Scott Sheppard, an astronomer who studies TNOs at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C., and was one of the first researchers to propose that a large planet might exist in the far-outer solar system, largely agreed with Tholen's take.

"We just do not have enough bona-fide distant ETNOs to have a good statistical argument for or against the clustering," he told Live Science.

"I would say we need to triple the current sample size of very distant ETNOs to have reliable statistics on the angles of these object’s orbits," Sheppard said. "If you do not have a large enough sample size, even if things are strongly clustered, the statistics will still be consistent with a uniform distribution simply because the sample size is too small."

Do you think there's a planet hiding inside the solar system?

Let us know in comments and help us spread ARSE into the deep unknown...

#Space_Aus