Space Junk Removal Thwarted by... Space Junk

Share

From the moment Sputnik 1 soared into the cosmos in 1957, humanity inadvertently began populating space with an assortment of space debris. From sizable space stations and large communication satellites to diminutive CubeSats, each launch has contributed to this ever-growing cosmic clutter. Even seemingly innocuous items like rocket fragments and paint flecks join the orbital accumulation.

The current state of affairs is cause for concern: there are over a million objects circling Earth that exceed the size of a centimetre, with an astounding minimum of 130 million millimetre-sized counterparts. Regrettably, the majority of this clutter won't be descending from its orbits anytime soon.

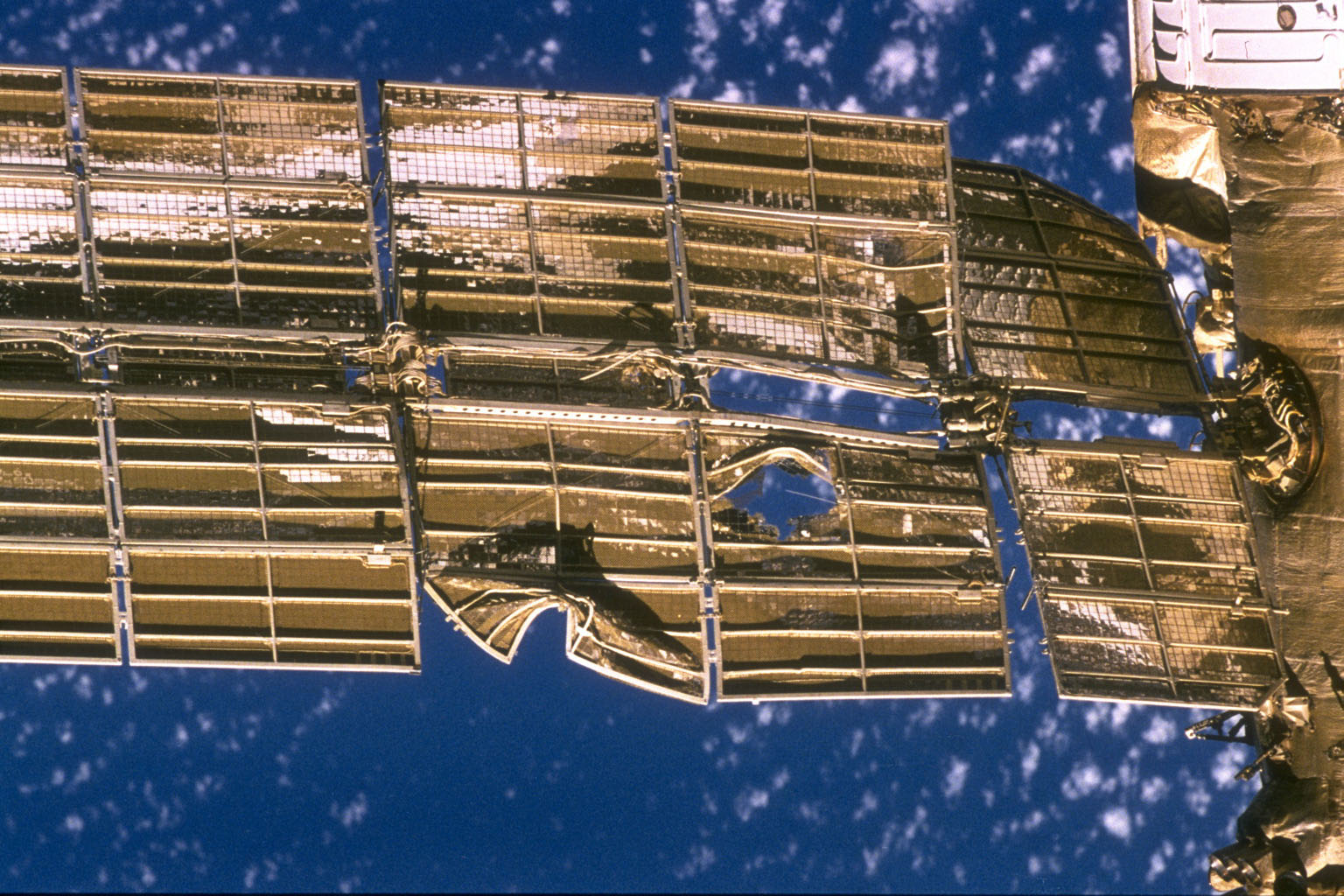

The situation has become so congested that the International Space Station (ISS) and other crewed missions must frequently adjust their trajectories to sidestep potential collisions. Instances of satellites colliding with debris have occurred, an occurrence that paradoxically begets more debris.

Should our current launch practices persist, we might confront a perilous scenario known as the Kessler cascade. This cascade sets off a chain reaction: collisions engender debris, which subsequently triggers more collisions. This relentless cycle can culminate in an orbital environment so jeopardised that sustaining operations becomes impracticable.

A map of debris orbiting Earth. (ESA)

This concept of a Kessler cascade has manifested in various fictional works, spanning from the manga "Planetes" to the movie "Gravity." In the latter, the cascade is depicted as an abrupt and dramatic occurrence, precipitated just hours following the obliteration of a test satellite by the Russians. However, the actual progression would likely be more gradual. Analogous to the unfolding of global warming, we understand that a tipping point awaits us unless we alter our practices. Regrettably, we remain uncertain about precisely where this threshold lies.

Thankfully, a series of initiatives are actively addressing this concern, among which is a collaborative endeavour between the European Space Agency (ESA) and Swiss startup ClearSpace.

Artist's impression of ClearSpace-1 capturing the upper part of a Vespa.

One promising strategy is championed by ClearSpace: systematically removing the most substantial and hazardous debris by capturing and subsequently deorbiting it. While smaller debris will persist as a challenge, removing these larger fragments can serve as a notable starting point.

The ESA is slated to launch a ClearSpace satellite in 2026, serving as a pilot mission. The primary objective revolves around capturing the Vega Secondary Payload Adapter (Vespa), a component left in orbit following a 2013 launch. Though it possesses a mass of around 100 kilograms and extends approximately 2 metres in length, Vespa isn't necessarily a critical hazard. However, its size and mass approximate those of more perilous satellites, rendering it a focal point for removal.

Yet, recent observations by the United States 18th Space Defense Squadron have yielded a surprise. An array of new objects now orbits in proximity to the Vespa adapter. These unforeseen additions likely resulted from the hypervelocity impacts of untracked fragments. This unforeseen complication underscores the intricate nature of the mission.

Despite this, the ClearSpace team maintains optimism that these fresh additions won't pose insurmountable challenges. The pilot mission for Vespa's removal remains on schedule. These developments underscore the burgeoning significance of projects like ClearSpace in an era where collisions between space debris and operational craft are intensifying. As the clock ticks, the urgency to devise comprehensive solutions heightens.

You’ve come this far…

Why not venture a little further into A.S.S. - our exclusive Australian Space Society.

And keep thrusting Australia into the deep unknown…

#Space_Aus