How Can We Perform Surgery in Space?

Share

Did you know a bloke in space got a blood clot in his neck?

While pretty common on Earth (affecting about 1 in 1000 people), this was a first in space.

Plus the clot was in his neck when they're usually in your lung (pulmonary embolism) or in the leg (deep vein thrombosis).

But in space?

Think deep vein thrombosis to the extreme and right below your brain...

The little but life-threatening clot was able to be sorted with injectable medication before it could do any serious damage.

This meant life and mission salvation for the poor fella who seems to be back to 100%.

As well as bringing up a pretty important issue:

If this bloke had to undergo surgery in space...

How the heck are we meant to do it?

This is super important as we inch closer to the reality of sending humans to Mars.

And more than likely to arise eventually on the six to eight-month journey to the crusty brown planet.

It gives us some pretty unique challenges.

Why is space surgery so hard?

Any serious injuries or unpredictable ailments mean Earth surgeons are 54.6 million km away... And that's when both planets' orbits are closest.

This is why the "bigger ups" in space think space surgery is "one of the main challenges when it comes to human space travel."

Currently, the go-to procedure from the International Space Station (ISS) is to maintain a stable condition in the patient then transport them planetside.

Obviously, this is a no from Mars.

Plus, there is a 20-minute time delay on communications so even if responsive on-site surgery was an option.

Oh and last but not least...

Mars has low gravity and high radiation so astronauts would need to be within a pressurised room or suit when operated on.

These factors take their toll on astronaut bodies even when surgery isn't required. Radiation changes astronaut cells while microgravity affects blood pressure and heart performance.

These are important for human homeostasis even when not performing surgery.

Oh and the heavily pressurised rooms make for an enclosed environment that bacteria just love, so infections can be common.

And to go a bit deeper...

Microgravity affects the bodies response to healing as weightlessness negatively impacts bone and muscle density. This means sick or weak astronauts have a much lower chance of surgery without complications.

How often do astronauts need surgery?

For a crew of seven people, researchers have estimated that the likelihood of one surgical emergency every 2.4 years.

Seven is the average we can agree upon for a trip to Mars.

Which is fine initially...

But!

A recent study you can find here notes that the minimum number of settlers needed to build and maintain a colony on Mars is 110.

This means when we inhabit the red planet the numbers drastically go up.

Another fun fact: the cost of colonising Mars is estimated to be US$10 trillion.

The most common emergency surgeries during a Mars mission would most likely be an acute injury, appendicitis, gallbladder inflammation or cancer. Even though astronauts are screened prior to travelling into space, the low gravity, radiation, and general nature of space can heighten sickness even in healthy people.

We have performed surgery in space although not on humans... Yet.

Astronauts have repaired severed rats tails and performed a laparoscopy which is a very low invasion surgery where organs are repaired inside the abdomen while in microgravity.

Again, not on a human.

So how will we perform surgery outside Earth?

Firstly, to perform a successful surgery we must address microgravity.

Starting with tools that need to be magnetised and stuck to the operating table to stop them from floating around.

The surgeon performing the surgery would need to be anchored in place too for obvious reasons, and most likely would be attached to the table.

That's great and all...

But previous attempts at surgery have a different issue altogether.

Guts would actually start floating out of the abdomen of patients in zero gravity. Also, blood would start to flow from the site of operation.

This means that surface tension will cause blood to stick to instruments

While not really life-threatening, this made for poor visibility for the surgeon.

Also, the circulating air of an enclosed room brings an infection risk.

The answer?

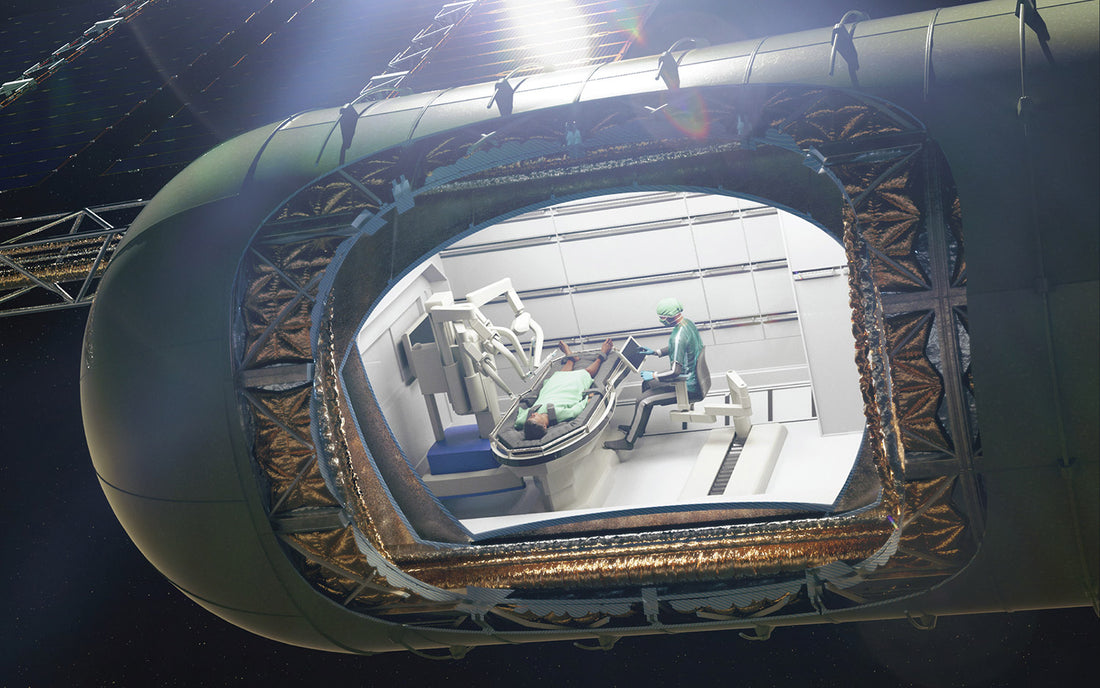

Answer 1: Trauma Pods

Minimally invasive surgeries or "keyhole" operations where only a small incision is used and the procedure is viewed through little cameras.

They'd also need to be performed in a type of bubble you see when people are quarantined in movies, kind of like a bubble.

Arms could then be put into bubble sleeves to perform the surgery and lessen the risk of infection.

This would all need to take place in a bigger building that shields the inhabitants from radiation.

It would also need many back-up materials and scientists have suggested 3D printers would be necessary for missions instead.

After all, equipment on a trip to Mars will only be the bare essentials for survival and scientific collection.

Answer 2: Robotic surgery

We have used robots in surgery one way or another for years on Earth. NASA has experimented with underwater simulations that mimic low gravity with success.

A remote-controlled robot successfully removed a gallbladder and kidney stone from a model abdomen.

The issue with this is the aforementioned 20-minute lag that the user would experience controlling the robot from Earth.

This avenue is still possible but would require innovation of our current technology to allow a same-time response from Earth to Mars.

Something that is beyond us for the foreseeable future.

Would you venture into Mars knowing surgery is not an option?

Let us know and share to spread ARSE!

#Space_Aus